November/December 2013

Memory MaintenanceBy James Siberski, MS, CMC; Carol Siberski, MS, CRmT, C-GCM; and Lauren Zack, OTD, OTR/L Cognitive rehabilitation can help patients achieve or maintain their optimum level of well-being and help reduce the functional disability resulting from the symptoms of cognitive impairment. In the United States, approximately 5 to 6 million adults have dementia, ranging from mild to severe. The vast number of baby boomers has prompted predictions that the population of individuals most likely to develop dementia—those aged 85 and older—will nearly double in the next 30 years.1 Boomers of all ages will flood practitioners’ offices with anxieties concerning their subjective cognitive losses and will seek reassurance and often a diagnosis from practitioners while searching for hope of identifying ways to retain or limit the erosion of their cognitive functions. Whether individuals are 45, 65, or 85 years old, hope is what’s required for people to become involved in a rehabilitation or prevention program for their cognitive abilities. Without hope, it’s unlikely these individuals will engage in any interventions, strategies, or therapies designed to prevent or at least slow cognitive decline. Physicians, physician’s assistants, nurse practitioners, or other therapists initiate the process of instilling hope and explaining what a patient can accomplish with cognitive rehabilitation. Currently, two goals are attainable. The first is the prevention or postponement of symptoms of a neurocognitive disorder (NCD), such as Alzheimer’s disease, where the disease is present in a person’s mid-50s, but the symptoms aren’t expressed for the next decade or even longer when it then can be said that the person has Alzheimer’s dementia. The second goal is to assist NCD patients to achieve or maintain their optimum level of well-being and personhood by helping to reduce the functional disability resulting from the symptoms of the disease and brain damage. This begins in the primary care physician’s office when a provider completes a comprehensive assessment of a patient who is anxious about a subjective memory problem or concerned about a perceived cognitive issue. This includes a physical and neurological exam, medication review, mental status exam, and cognitive and neuropsychological testing. If the results are normal, the patient can be counseled on lifestyle changes that he or she can make to maintain or improve cognition, and perhaps be directed to a beneficial reference such as The Alzheimer’s Prevention Program: Keep Your Brain Healthy for the Rest of Your Life coauthored by Gary Small, MD, director of the UCLA Longevity Center. Patients also should know that their baseline data can be monitored over time to note any changes in condition or status. Making a Diagnosis The physician should provide both the patient and family with information about future expectations, available treatments, creating therapeutic and lifestyle plans, and details about what the patient and family can hope for in the future. The physician can suggest educational resources from numerous sources. For instance, Age Pages offers free health care information provided by the National Institute on Aging (www.nia.nih.gov/health/publication?tid=All&field_pub_type_value=AgePage&tid_1=). The Alzheimer’s Association furnishes information on Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, Lewy-body dementia, frontotemporal dementia, Huntington’s disease, mild cognitive impairment, normal pressure hydrocephalus, Parkinson’s disease dementia, traumatic brain injury, and vascular dementia (www.alz.org). Providers also can evaluate and prescribe medication as appropriate. Once again, it’s ideal to educate patients and their families regarding the risks and benefits related to medications and the expected outcomes. Treating any comorbid medical or psychiatric conditions will enable patients to achieve or maintain their optimum level of well-being and personhood by helping to reduce functional disability. Whenever possible, reducing anticholinergic medications that can negatively impact the cognitive abilities of older patients and patients with NCD will aid in the rehab process. Assessing patients’ sensory systems is crucial to the rehab process. If a patient is unable to hear or see, for example, he or she isn’t making sensory memories and consequently fails to create any short- or long-term memories. Evaluate hearing, sight, touch, taste, and smell and, if a possible impairment is discovered, consider referring the patient to the appropriate specialist. Making a diagnosis, conducting a medication review, prescribing medication, and assessing and correcting sensory deficits form the cornerstone of cognitive rehabilitation. Taking Action Establishing memory fitness centers provides older adults with the opportunity to slow memory decline and other cognitive functions associated with aging, preserve and maintain their functional level and, through a variety of mentally and physically stimulating activities, enhance some areas of cognition that through disuse have become less efficient. Cognitive enhancement in these areas helps to promote a higher quality of life. Whether it occurs in a physician’s office or at one of these clinics, education informs individuals of healthful choices that promote an efficient mind. Such educational topics can focus on diet and nutrition, vitamins, relaxation techniques, and stress management techniques. Research suggests that by participating in these types of activities, individuals who are cognitively intact will preserve memory, and those who have cognitive deficits will maintain their current status longer and potentially enhance their brain function to restore some of their independence and abilities. Once a patient has the information, he or she can decide personally whether it is worthwhile to engage in therapy in order to extend cognitive life span to equal the natural life span. In the absence of a convenient cognitive rehab clinic, a practitioner’s office can offer suggestions designed to help patients achieve their goals related to cognitive health. Keep in mind that cognitive health requires that patients engage in programs and activities chosen in an attempt to identify a “just-right challenge,” with the goal of presenting a challenge with activities that are not so difficult as to discourage participation. (See below for a patient handout that can be valuable in guiding patients to maintain cognitive function.) As previously noted, a provider can recommend that a patient engages in a computerized program that can enhance cognitive functioning. Brainiversity software, for example, which is inexpensive and easy to use, can be purchased online (www.brainiversity.com). When the conversation turns to computerized cognitive training programs, patients often ask practitioners whether the programs are effective and beneficial. In studies where pre- and postprogram test results are examined, it appears that such programs do work. However, determining whether the success of various computer programs can be generalized or whether computer exercises translate to improvement in activities of daily living is a difficult proposition. Studies have shown that this type of intervention may work in patients with chemo brain,2 has mixed results in patients with schizophrenia,3 and has been used to improve attention and memory in older adults following coronary artery bypass graft surgery.4 Other studies also indicate improvement in both healthy and cognitively impaired older adults.5 Some studies display weaknesses such as design flaws and small sample sizes. While there is evidence that computerized cognitive interventions are beneficial in the cognitively healthy community-dwelling older adult and the cognitively impaired older adult, future research is necessary. As with any treatment, a cognitive program must be carefully selected and providers should conduct a risk/benefit discussion with the patient. The provider should consider the positive aspects of the patient adopting a constructive activity to engage in (ie, the patient using computer-based programs plays an active role in the treatment process and accepts responsibility for his or her own progress). A recent demonstration highlighted a program designed to determine the feasibility of developing a memory clinic in a nursing facility. Initially, there were 10 participants, and data were gathered on participants who completed the six-week program with twice-weekly sessions. During every session in which each module continued for approximately 15 to 20 minutes, the three primary components included computer brain-training exercises and puzzles; table-top pencil and paper activities such as word scrambles, word searches, and hidden pictures; and social/educational discussions. Participants utilized the Brainiversity computer program, designed to stimulate the brain, keep track of users’ progress, and allow users to unlock additional activities as they complete the ones initially available. Participants took daily exams and then chose activities in which to participate. Individuals varied in familiarity with computer usage as well as the speed in using the mouse and keyboard. Therefore, some users completed more activities than others while some completed only the daily exam, the daily exam plus one activity, or multiple activities. Overall, the participants reported enjoying the program and the incorporated activities. The participants who completed the program inquired about and expressed interest in taking part in the program in the future. The table below depicts the pre- and postprogram test scores of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment for four participants who consistently attended the program sessions. Consistency is critical to the degree of patient success during the experience. Clinicians should underscore the importance of regularly performing the activities if the patient hopes for positive results.

— Source: Lauren Zack, Capstone Project The point is that a patient who decides against regularly using a simple-to-install, easy-to-use program costing less than $15 also will not use a more expensive program with more bells and whistles. Providers can start patients on a simple program such as Brainiversity, and can recommend a more sophisticated program when patients achieve the maximum benefit, become bored, or are no longer challenged. It is important to tell patients that just like medications, cognitive function improvement takes time. If clinicians show interest in patients’ progress regarding this and other tasks, patients will have more hope that their efforts will be beneficial to their cognitive health. However, patients should recognize that failure is part of success. If they score 100% on all the exercises all the time, then little is being accomplished. Patients need to understand that they may fail at first and then improve, and that when the degree of difficulty is appropriately intensified, there again will be a degree of failure. As stated earlier, a patient who engages in cognitive enhancement programs needs to be presented with an appropriate level of challenge in order to be stressed but not with programs or activities so difficult that he or she could become discouraged from participating. Higher functioning patients—for example, those with advanced degrees or previously demanding vocations—will have a difficult time with this concept, as they are accustomed to success and may abandon the program under the guise of needing to visit the restroom and may not return. It is imperative that practitioners clearly explain the trial-and-error or failure-and-success concept to maximize the prospects of overall success in terms of cognition. Case Study She participated in all 12 memory fitness center program sessions. Her cognitive assessment score increased from 22 (mild cognitive impairment) to 27 (normal cognition). On the computer program, she completed the daily exams plus seven additional activities. Her scores increased on the activities she completed more than once. She reported enjoying the program activities and inquired about locating similar puzzles to work on during free time following the program’s conclusion. Although Amy was not diagnosed with an NCD, she was not utilizing her cognitive abilities, causing them to atrophy. Suggesting ways to improve cognitive function provides hope to cognitively anxious patients who are experiencing any stage of an NCD as well as to families and caregivers who are attempting to cope and find some hope in an older adult’s cognitive condition that can seem hopeless. — James Siberski, MS, CMC, is the coordinator of the Gerontology Education Center for Professional Development as well as an assistant professor of gerontology at Misericordia University in Dallas, Pennsylvania. He also is an adjunct professor of psychiatry at Penn State University. — Carol Siberski, MS, CRmT, C-GCM, is a geriatric care manager in private practice and participates in research in geriatrics and intellectual disabilities. — Lauren Zack, OTD, OTR/L, is an occupational therapist in a skilled nursing facility and an adjunct faculty member at Misericordia University.

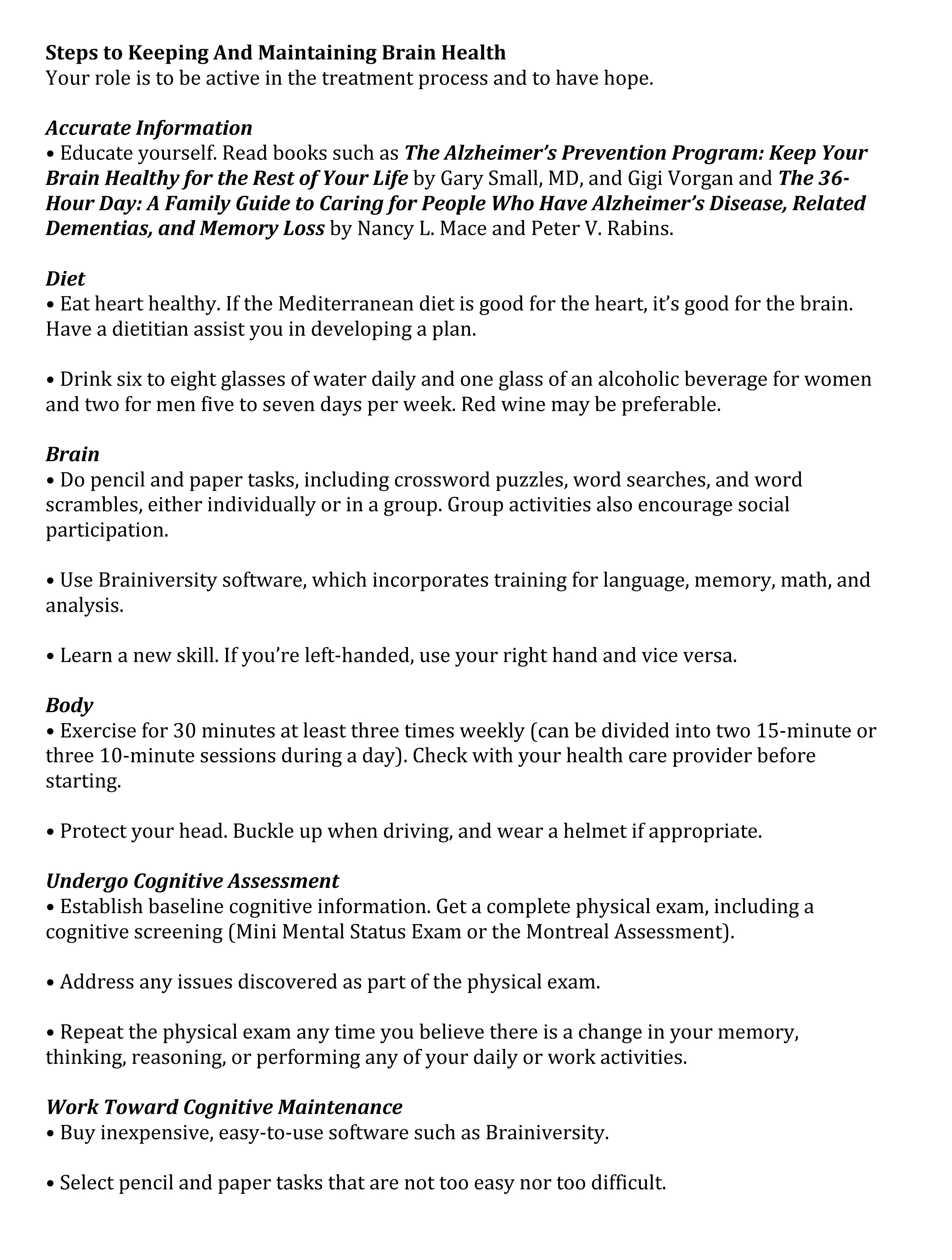

Patient Handout: Steps to Keeping and Maintaining Brain Health

References 2. Ferguson RJ, Ahles TA, Saykin AJ, et al. Cognitive-behavioral management of chemotherapy-related cognitive change. Psychooncology. 2007;16(8):772-777. 3. McCall B. Computerized training boosts cognition in schizophrenia. Medscape website. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/762943. April 30, 2012. 4. de Tournay-Jetté E, Dupuis G, Denault A, Cartier R, Bherer L. The benefits of cognitive training after a coronary artery bypass graft surgery. J Behav Med. 2012;35(5):557-568. 5. Eckroth-Bucher M, Siberski J. Preserving cognition through an integrated cognitive stimulation and training program. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2009;24(3):234-245.

|