July/August 2015

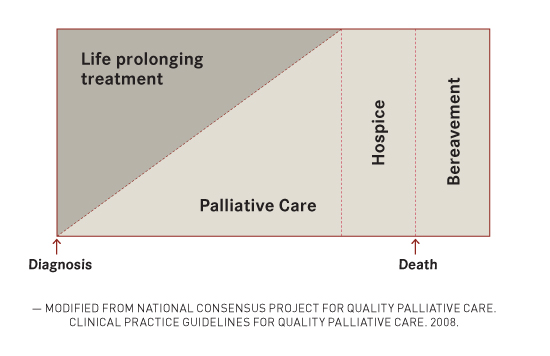

Insight and Information Are Key to Implementing Palliative Care Palliative care focuses on patients' quality of life, recognizing their individual goals and values. Care centers on the individual at the time of initial diagnosis as well as over the course of active curative treatment and through the challenges of patients' clinical course. Palliative care is one of the fastest growing fields in medicine, and fueling this growth is a mounting body of evidence supporting the benefits of palliative care involvement in patients with serious or life-threatening illness. By 2050 more than 20% of the US population will be over the age of 65, and with this surge in baby boomer numbers comes an inevitable increase in the number of adults facing serious and life-threatening situations. Despite this anticipated need, palliative care remains widely misunderstood and stigmatized—not only by patients and their families but also by health care professionals. What, then, is palliative care really about, and how do we as health care professionals engage our patients and their families in something as sensitive and emotional as an end-of-life conversation? Case Report Does this situation sound familiar? Deborah and Rich are about to start a new chapter in their lives, one with twists and turns and complicated decisions—decisions that may, at times, conflict with her personal goals and values. Would now be an appropriate time to involve palliative care? Or should we wait until Deborah is closer to the end of life? The answer: Now is the perfect time to involve palliative care. But this often fails to occur because talking about things like death and dying is difficult and fraught with emotion, and because palliative care is often considered a synonym for hospice and "giving up." The reality of what palliative care tries to accomplish is quite different. Concurrent Care This concept of concurrent care is key to the understanding of what palliative care entails. Palliative care focuses on a person's quality of life, including his or her individual goals and values and what it means to live with a terminal illness. It is care focused on the patient as a person, not only at the time of initial diagnosis but also during active curative treatment and through all the ups and downs of the patient's clinical course. In fact, just because palliative care is involved doesn't mean a patient is appropriate or even eligible for hospice. In Deborah's situation, many would argue that now, at the moment of diagnosis, is the ideal time for the involvement of palliative care, and there is evidence to support this suggestion. The landmark New England Journal of Medicine study in 2010 by Temel and colleagues showed how early palliative care involvement not only improves quality of life and symptoms of anxiety and depression but also improves survival in patients with lung cancer. In addition, studies have shown that people want to talk about and plan for living with a life-limiting illness. They want to explore their options and prepare themselves and their loved ones for what will inevitably come. How, then, might the involvement of palliative care help Deborah at the start of her life with cancer? Consider the following titration model of palliative care involvement:

At the time of diagnosis, palliative care may simply serve as another form of support, not only for Deborah but also for Rich. Palliative care provides a multidisciplinary approach to the management of suffering, whether it's physical suffering from symptoms such as pain or nausea, or emotional/spiritual/existential suffering. Palliative care physicians work closely with palliative nurses, social workers, chaplains, therapists, dietitians, patient care aides, and many other health care professionals to provide complete care of the patient as a person. As a patient's illness progresses, the involvement and support of palliative care is titrated to his or her needs and may ultimately transition into the utilization of hospice as death approaches. But those initial patient visits, as in Deborah's case, often involve little more than simple conversations about who they are—what they value in life, what they hope to achieve with what time remains, what makes them happy, what gives their lives meaning. We try to provide as much support as possible so that patients never have to sacrifice this meaning, even in the middle of a grueling course of treatment. We listen and use empathic techniques to support and process the complicated emotions that surround death and dying, and try to identify what it means for our patients to live better even as they face death. And we help focus their time and attention on what is most important in life, and make sure their health care providers formulate a medical plan that reflects these goals and values. A life facing death often seems devoid of choice and control, but as Oliver Sacks wrote in his recent New York Times article, "It is up to me now to choose how to live out the months that remain to me. I have to live in the richest, deepest, most productive way I can." Some health care professionals are reluctant to involve palliative care early, not only because of the above misconceptions but also because of the assumption that patients don't want early palliative care. In addition to this assumption, it is often easier to discuss "positive" things such as fighting the cancer and "fixing" the situation rather than addressing more emotional, sensitive subjects such as end-of-life planning and what might happen if the situation can't be "fixed." The reality of a life-limiting illness is, simply put, that life is limited. In light of this fact, the goals often shift to living as well as possible for what time remains in the context of our values. For many people this means hoping for the best while preparing for the worst, and it is with this preparation and the anticipation of things to come that palliative care provides guidance. Hoping for the best and preparing for the worst helps patients live better in the here and now. It can help them feel secure in knowing that they are focusing on what matters most in life and comforted by the fact that they have a plan in place if things get worse. Engaging Patients Palliative care, therefore, may be offered as another form of support or a way to ensure that our patients are being treated first and foremost as people and not as cancer or dementia or stroke. It offers a way to ensure that our patients are making the most educated and informed decisions based on their individual goals and values rather than based on what health care professionals think is best. Palliative care is about Deborah—about her life, about spending time with her family, about treating her cancer with chemotherapy if that is her decision, and maximizing her quality of life while she undergoes treatment. But it is also about exploring some of the really terrifying things that come with cancer and helping to realize when continuing aggressive treatment is no longer aligned with her goals and values. Let's check back in with Deborah. The palliative care team spends the initial visit getting to know Deborah and Rich better. Deborah is hoping to make it to the big family reunion at the end of the year and is hoping to meet some of her great-grandchildren for the first time. She loves her family dearly and misses gardening. She is worried about how Rich will cope after she dies. Rich seems very concerned about Deborah's pain and the results of her most recent CT scan. On further exploration, it's clear that Rich is quite fearful of losing Deborah and is already starting to grieve in anticipation of her death. Over the next several visits, Deborah's pain worsens and she is becoming more dependent on Rich for her activities of daily living. A repeat CT scan shows that the cancer has spread despite chemotherapy. The palliative care team adjusts her pain medication, and Deborah begins second-line palliative chemotherapy. As a result, she finds that she is spending most of her time in the hospital and the clinic rather than at home with her family. The palliative care team sits with Deborah and Rich, and they explore her understanding of her prognosis and what would be most important to her in the time that remains. They learn that Deborah is tired of being sick. She feels she has lived a good life and does not want to spend the time and energy she has left battling pain and nausea and traveling back and forth to the hospital. She wants to be at home and feel as good as possible for the upcoming family reunion. She doesn't want to continue chemotherapy. Based on her goals and values, the palliative care team helps prepare her advance directive and medical power of attorney documentation. Given the rapid progression of her cancer and her functional decline, the palliative care team believes she has a prognosis of less than six months and recommends hospice so that she can stay at home as comfortably as possible for as long as possible. She enrolls in hospice and is able to attend the family reunion. She dies several months later at home, surrounded by her family. Through early palliative care involvement and titrated support, the medical team was able to learn more about Deborah's individual goals and values and created a plan of care that reflected these values in real time. This is the essence of palliative care: getting to know our patients better as people and supporting whatever it means for our patients to have quality and meaning in their lives while we provide guidance in emotionally overwhelming times. These elements hopefully are not unique to palliative care. We would argue that these are things that all health care professionals should do regardless of specialty or position. Perhaps the most important thing we can do to maximize quality at the end of life is to determine what quality means for our patients and fight for and recommend this, just as we would recommend an MRI for a suspected stroke or a chemistry panel for renal failure. Meeting the Challenge The future of palliative care is bright, from growing public interest demonstrated by the success of books like Atul Gawande's Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End to increasing research and integration into social media. Providing patient-centered care and focusing on our patients as people must be the standard of care because no two people are alike and because we all deserve to live every moment of our lives as we see fit until the moment we die. — Andrew Thurston, MD, is a clinical assistant professor of medicine and the medical director of palliative care at UPMC-Mercy Hospital in Pittsburgh. — Robert Arnold, MD, is a professor of medicine and chief of the Section of Palliative Care and Medical Ethics at the University of Pittsburgh, chief medical officer of the UPMC Palliative and Supportive Institute, and a founding member of VitalTalk. |