Fall 2025

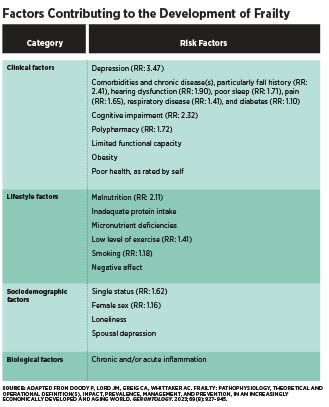

Fall 2025 Issue Beyond Aging How Identifying and Addressing Frailty Can Transform Care Along with sarcopenia, anorexia of aging, and cognitive impairment, frailty is one of the modern Geriatric Giants—a set of syndromes that increase risk for falls, hip fractures, mood disorders, and delirium.1 Specifically, frailty is a syndrome that leaves an individual more vulnerable to stressors in multiple body systems due to a decline in cognitive, psychosocial, and physical capabilities.2 Frailty and the other Geriatric Giants are also associated with substantially increased health care costs and adverse outcomes, including disability, hospitalization, nursing home admission, and death.1,2 Prevalence estimates vary widely because definitions and diagnostic tools are inconsistent. Overall, 12% to 24% of older adults are estimated to be frail.2 More specifically, about 10% of community-dwelling adults aged 65 and older are frail, with prevalence rising to 25% to 50% of those aged 85 and older. In acute care, nearly one-half of hospitalized seniors are frail, and in nursing homes, about half of residents are frail, while another 40% are prefrail.3 Frailty risk is worsened by comorbidities, physical inactivity, poor nutrition, and other factors.4 Women have higher frailty indices than men at every age, with the gap continuously widening after age 75.5 With the global population aging, the number of frail individuals requiring health care is rapidly rising, creating a serious public health challenge.4 Although frailty progresses at an average rate of 3% to 6% annually, it can sometimes be slowed or even reversed with targeted interventions.5 Most importantly, frailty may be prevented when screening and intervention occur during robust or prefrail states.4 Understanding Frailty Defining and Diagnosing Frailty Frailty involves both physical and psychosocial components and can be assessed through several tools. The most common tools used in research are: Fried’s Frailty Phenotype, which assigns an individual a frail phenotype when they meet three or more of these five criteria: unintentional weight loss, weakness or poor handgrip strength, self-reported exhaustion, slow walking speed, and low physical activity. Rockwood’s Frailty Index, which provides a continuous score from one through nine, shows an individual’s accumulation of deficits across more than 60 health-related variables. A person is considered frail with a score of five or higher.3-5 Pathophysiology and Risk Factors The table below provides an overview of the major risk factors that have been associated with the onset and progression of frailty, including their relative risks where available.4,8 These factors span nutrition, physical activity, medical conditions, and social circumstances, emphasizing that frailty is not an inevitable consequence of aging but a condition shaped by multiple influences. Interestingly, BMI was not associated with increased risk of frailty, likely because BMI alone is not an accurate predictor of muscle mass. As well, although most frail individuals were older than nonfrail individuals in the studies reviewed, this was not always the case, showing that factors other than age are more closely correlated with the onset of frailty.8 The Central Role of Nutrition in Frailty That said, frailty is not limited to undernutrition alone. Obesity also elevates risk, particularly when excess weight is accompanied by reduced muscle mass and higher body fat percentage. These patterns highlight the dual role of both insufficient and imbalanced nutrition in driving vulnerability.2 Taken together, the evidence underscores that optimizing nutritional intake is central to maintaining strength, independence, and robustness in aging. Dietary Patterns The inflammatory potential of the overall diet also appears to be critical. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet—emphasizing plant-based foods, olive oil, and reduced intake of meat and dairy—has been shown to reduce frailty risk across Mediterranean and US populations.2 As well, higher scores on the Dietary Inflammatory Index are linked to elevated circulating inflammatory markers and a greater likelihood of frailty, even after accounting for age, comorbidities, physical activity, and energy intake. Finally, limiting ultraprocessed foods is important, as these displace nutrient-dense options while contributing to adverse outcomes such as cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, and cancer.2,6 Protein and Muscle Health Micronutrients and Polyphenols Evidence regarding the impact of vitamin B12 and folate is also mixed, with some studies showing an association between deficiencies and frailty, while others do not. Nonetheless, given their essential roles in metabolism, methylation, and immune regulation, adequate intake is critical for supporting overall health. Calcium and vitamin D are also key for bone and muscle health, and supplementation in older adults has been linked to improved gait speed and muscle strength.6 Because micronutrient interactions are complex and synergistic, and research studying one or two micronutrients has been inconclusive, focusing on a single nutrient may not be effective. In one study, combined supplementation with folate, calcium, and vitamins B6, B12, and D improved frailty outcomes in community-dwelling older adults.6 However, this level of supplementation may not be feasible in most care settings or for older individuals living at home. Ultimately, a nutrient-dense, wholefoods diet remains the most reliable approach to ensuring adequate intake of the micronutrients and polyphenols that can help reduce the risk of frailty development and progression. Nonnutritional Contributors to Frailty Physical Inactivity Across all life stages and levels of frailty, regular exercise protects against multiple frailty risk factors, including its ability to improve muscle strength, mobility, cognition, and mood. Thus, physical activity is as essential as nutrition in managing frailty.1,4 In fact, research consistently shows that the combination of exercise and nutrition can limit frailty progression and, in some cases, even reverse it.4 Interventions such as resistance training, balance exercises, and aerobic activity have all been shown to improve strength, gait speed, and balance in older adults when appropriately implemented. To achieve the greatest benefit, exercise plans should be tailored to each individual for safety and feasibility, especially in prefrail or frail adults.4 Cognitive and Psychological Factors Evidence also points to a bidirectional relationship between frailty and cognitive decline. Studies show that an increase in frailty can accelerate cognitive impairment, while declining cognition can, in turn, exacerbate frailty. Shared mechanisms such as oxidative stress and chronic inflammation may help explain this interplay.6 Similarly, depression and frailty appear to influence one another. Older adults with major depression, a family history of depression, or moderate to severe depressive symptoms face a higher likelihood of developing frailty, independent of age, gender, or pain status.15 These findings highlight the need for holistic approaches that address both physical and psychological wellbeing in efforts to prevent or slow frailty progression. Polypharmacy and Medical Burden Older adults with reduced functional reserve are particularly vulnerable, as multiple medications may increase the risk of weight loss, balance difficulties, malnutrition, and loss of independence.16 Regular medication reviews by qualified health care practitioners are essential to minimize duplication, optimize dosages, and reduce unnecessary prescriptions.15 Slowing Frailty Early Screening and Identification Although Fried’s Frailty Phenotype and Rockwood’s Frailty Index are widely used research tools, they are often impractical for routine health care settings. A more feasible alternative is the FRAIL scale, which asks patients to self-assess the following five criteria: Fatigue: Are you fatigued? For practitioners working in long term care, the FRAIL-NH offers additional specificity, accounting for population-specific conditions, such as altered diets and the need for assistance with dressing.18 Incorporating these screening tools into routine care allows health care professionals to detect frailty risk earlier, opening the door for timely interventions to slow or even prevent progression. Multimodal Intervention For instance, pairing resistance and aerobic exercise with adequate protein and calorie intake helps preserve muscle mass and functional capacity more effectively than either strategy alone.4 Likewise, careful review of medications reduces the risk of side effects that worsen physical decline.15 Addressing psychological and cognitive health is equally important, as depression, anxiety, and cognitive impairment can reduce motivation, limit participation in activities, and accelerate functional loss.1 By combining physical, nutritional, medical, and psychosocial supports, interventions can reinforce one another and create a stronger foundation for resilience. This coordinated approach allows practitioners to intervene earlier and more effectively, with the goal of slowing or even reversing frailty. Multimodal strategies maximize the opportunity to maintain independence, protect quality of life, and extend healthy lifespan in older adults. Coordinated Care Approach Conclusion — Stephanie Dunne, MS, RDN, IFNCP, is an integrative registered dietitian, freelance writer, and owner of Feed Your Intention in St Petersburg, Florida.

References 2. Lochlainn MN, Cox NJ, Wilson T, et al. Nutrition and frailty: opportunities for prevention and treatment. Nutrients. 2021;13(7):2349. 3. Le Pogam MA, Seematter-Bagnoud L, Niemi T, et al. Development and validation of a knowledge-based score to predict Fried's frailty phenotype across multiple settings using one-year hospital discharge data: the electronic frailty score. EClinicalMedicine. 2022;44:101260. 4. Doody P, Lord JM, Greig CA, Whittaker AC. Frailty: pathophysiology, theoretical and operational definition(s), impact, prevalence, management and prevention, in an increasingly economically developed and ageing world. Gerontology. 2023;69(8):927-945. 5. Theou O, Haviva C, Wallace L, Searle SD, Rockwood K. How to construct a frailty index from an existing dataset in 10 steps. Age Ageing. 2023;52(12):afad221. 6. O’Connor D, Molloy AM, Laird E, Kenny RA, O’Halloran AM. Sustaining an ageing population: the role of micronutrients in frailty and cognitive impairment. Proc Nutr Soc. 2023;82(3):315-328. 7. Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, et al. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing. 2019;48(1):16-31. 8. Wang X, Hu J, Wu D. Risk factors for frailty in older adults. Medicine. 2022;101(34):e30169. 9. Coelho-Júnior HJ, Milano-Teixeira L, Rodrigues B, Bacurau R, Marzetti E, Uchida M. Relative protein intake and physical function in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutrients. 2018;10(9):1330. 10. Bauer J, Biolo G, Cederholm T, et al. Evidence-based recommendations for optimal dietary protein intake in older people: a position paper from the PROT-AGE Study Group. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(8):542-559. 11. Baum JI, Kim IY, Wolfe RR. Protein consumption and the elderly: what is the optimal level of intake? Nutrients. 2016;8(6):359. 12. Coelho-Júnior HJ, Rodrigues B, Uchida M, Marzetti E. Low protein intake is associated with frailty in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Nutrients. 2018;10(9):1334. 13. US Department of Agriculture; Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2021-03/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans-2020-2025.pdf. Published December 2020. 14. Moore DR. Keeping older muscle “young” through dietary protein and physical activity. Adv Nutr. 2014;5(5):599S-607S. 15. Oyon J, Serra-Prat M, Limon E, et al. Depressive symptom severity is a major risk factor for frailty in community-dwelling older adults with depression. A prospective study. Fam Pract. 2022;39(5):875-882. 16. Alqahtani, B. Number of medications and polypharmacy are associated with frailty in older adults: results from the Midlife in the United States study. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1148671. 17. Ruiz JG, Dent E, Morley JE, et al. Screening for and managing the person with frailty in primary care: ICFSR consensus guidelines. J Nutr Health Aging. 2020;24(9):920-927. 18. Kaehr EW, Pape LC, Malmstrom TK, Morley JE. FRAIL-NH predicts outcomes in long term care. J Nutr Health Aging. 2016;20(2):192-198. |