July/August 2018

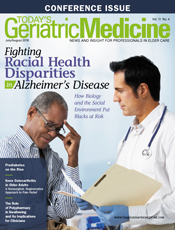

From the Editor: A Legacy of Shame Bad blood. That was the diagnosis given to participants in a heinous experiment begun in 1932. It's an apt description of the legacy of what was arguably the most unethical chapter in American medicine, the devastating repercussions of which continue to ripple through American research and medicine. The Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male began with 600 Alabaman black men, mostly illiterate, 399 of whom had syphilis, and 201 who did not. These men, who were recruited on the promise of free treatment, did not give informed consent and were advised neither of the purpose of the study nor of its hazards to them and their families. The premise of the study was to determine whether the available treatment—a largely ineffective, toxic, and even sometimes fatal combination of mercury and bismuth—was better than no treatment. The men were led to believe they were being treated for bad blood—a nebulous term that appears to have gone unexplained—when in fact treatment was withheld from them. Researchers merely periodically assessed them and observed their horrific deterioration. Fifteen years after the study began, the cure for syphilis—penicillin—became known. The scientists conducting the study, however, withheld that cure from the participants, allowing their disease not only to progress but to be spread to wives and children. Inconceivably, the study continued until 1972, when the New York Times revealed that the participants had been untreated and left to languish. The following year, Congressional hearings were held and a class action lawsuit was filed. The next year, an out-of-court settlement was made, awarding $10 million to participants along with promises of lifetime medical care. By that time, however, 120 participants had died from syphilis or related diseases, and 40 of their wives and 19 of their children had been infected. That same year, to prevent such unethical mistreatment, Congress passed the National Research Act, and the modern era of medical ethics was born. As Ian McDonough, PhD, discusses in our cover story, "Fighting Racial Health Disparities in Alzheimer's Disease," after revelations about the study, mistrust of medical research and practitioners among blacks was widespread and remains to this day in some communities. This erosion of trust led to an unwillingness to participate in medical research, which in turn contributed to diminished outcomes. McDonough, an assistant professor in the psychology department at the University of Alabama and an associate of the Alabama Research Institute on Aging, reminds physicians of their responsibilities and of the lessons that continue to be learned from the Tuskegee experiment, urging scientists and minority community members to partner to eliminate health disparities that can be traced to the unethical treatment of the black men of Tuskegee. |