January/February 2017

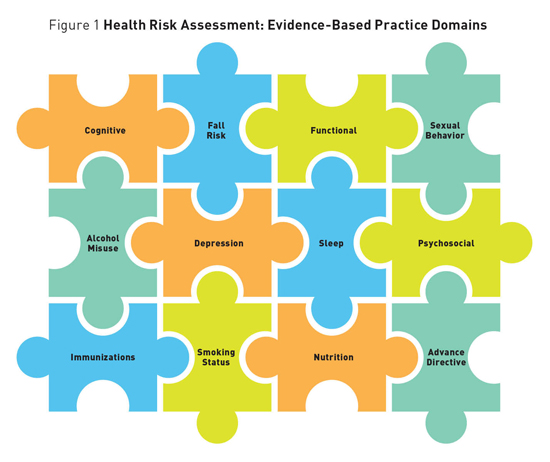

System-Level Strategies for a Value-Based Medicare Annual Wellness Visit Implementing the Medicare Annual Wellness Visit requires prioritization, team-based support, and processes aligned to value-based care in the health continuum tied to evaluations of health outcomes with personal prevention. In 2011, the Affordable Care Act outlined coverage for a Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Annual Wellness Visit (AWV) and a call to action by CMS Administrator Donald Berwick, MD, emphasized the health care provider's (HCP) role in helping patients understand the importance of prevention.1,2 Outlined by CMS, requirements of the AWV mandate providers conduct a health risk assessment, provide prevention/health promotion consultation, develop a personal prevention plan (PPP) with the patient, and provide him or her with a written PPP. Although CMS has for the first time committed to paying providers for comprehensive alignment of preventive screening and services, less than 24% of fee-for-service Part B and 14% of Medicare Advantage Medicare beneficiaries received the AWV in 2015.3 A recent descriptive study, "Relationship Between Health Care Practitioner Characteristics and Comfort Level With the CMS Medicare Annual Wellness Visit," aimed to explore characteristics and comfort levels of 90 health care practitioners who provide preventive services to Medicare beneficiaries vs those who do not.4 The authors evaluated characteristics and evidence-based practice behaviors of 12 health risk assessment domains, which are described below, and further evaluated the HCPs' work environments and organizational strategies.4 Evidence-Based Practice Domains The study results revealed HCPs who conducted AWVs were more likely to measure patient outcomes in the domains of depression, fall risk, sleep, and nutritional assessment (p <0.05).

Work Environments Organizational Strategy Discussion Prioritization Tips that will be useful in developing prioritization include the following: • develop a standardized AWV template that asks the evidence-based questions that support health risk assessments and personal prevention plans; • match health risk assessment AWV domains with evidence-based quality metrics, including all 12 domains (cognitive, depression, functional, fall risk, psychosocial, alcohol misuse, sleep, sexual behavior, nutrition, immunization, advanced directive, and smoking status); • consider HCP scorecard metrics—population-based tools to identify eligible patients; • utilize the AWV to foster patient engagement, patient activation, and shared decision-making; and • create a consumer awareness campaign. Team-Based Support Plans for developing team-based support can be enhanced by the following: • promoting interprofessional team education, including purpose, team member roles, risk factors for older adults, preventive measures, and reimbursement/coding; • building AWV into the previsit team planning processes; • developing goals with the patient as part of the PPP regarding disease prevention efforts; • leaving schedules open for one year ahead to schedule subsequent visits (eg, chronic care management, subsequent AWV); and • considering alternative care sites, such as telehealth and home visits. Process Alignment

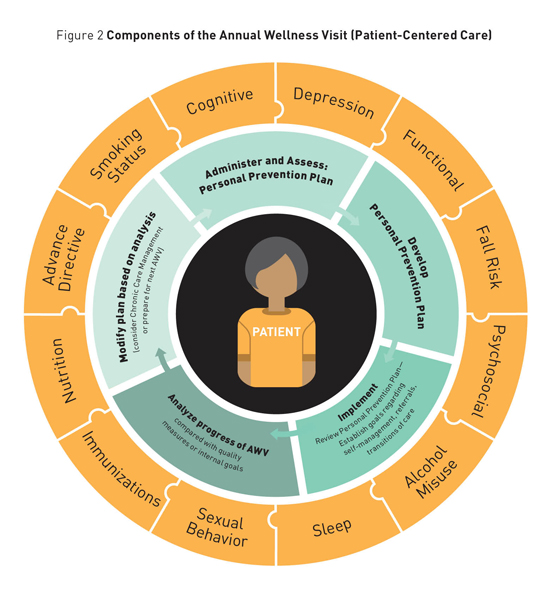

Incorporating system/office-based process alignment and the framework of implementation science is essential to address the gaps in care delivery supporting the AWV, as gaps to the AWV uptake nationally have been attributed to provider time constraints, documentation, and overall lack of awareness of Medicare beneficiaries regarding coverage and purpose.9 Important recommendations for improving process alignment include the following: • administer the health risk assessment to every eligible patient; • review and develop personal plans, providing a written PPP to the patient; • implement/establish goals regarding self-management, transitions of care, and referrals; • analyze progress, comparing to quality measure or internal goals; • modify plan based upon analysis (produce a risk mitigation report, risk stratify the population based upon risk categories defined); and • build a care pathway to impact patient outcomes and improve patient experience, with a focus on reducing overall cost of care. Organizational Case Study The organization developed a multistate marketing campaign targeting patients to ask their providers to schedule an AWV. The campaign produced banners, posters, table tents, trifold brochures, and postcards. For the health team members, organizers developed a toolkit that includes talking points and scripts, optimized the electronic health record by building a smartset, added the AWV completion rate to dashboards and scorecard metrics, and included bonuses for executives who meet completion targets. In 2016, BSHSI's AWV rate was 55%. Best practices in adult immunizations when achieving a 40% AWV completion rate were associated with an 84.5% pneumonia vaccinate rate compared with a 53.6% pneumonia vaccinate rate in those without an AWV. Additionally, 30% more beneficiaries were screened for colon and breast cancer when comparing those who received vs those not receiving an AWV. While the causal relationship is unclear, there is a significant difference in quality measure performances between those beneficiaries who received an AWV vs those who did not. Summary Medicare beneficiaries deserve the opportunity to receive an AWV with emphasis on all 12 domains of care referenced in this article. An evidence-based practice, the value-based AWV offers Medicare beneficiaries the opportunity to prevent disease and disability and slow the progression of chronic disease. In this era of value-based care where measurement of outcomes, costs, and processes are critical, embracing an organizational AWV strategy is a crucial investment. — Lisa D. Wright, ANP-C, DNP, CPHQ, is an associate director at Merck and adjunct faculty at Jefferson College of Health Sciences at Carilion Clinic in Roanoake, Virginia. Her clinical interest includes prevention/wellness strategies and population health. — Kathie Zimbro, PhD, RN, is the nurse executive for research for Sentara Healthcare and an adjunct associate professor with the DNP Advance Practice Program at Old Dominion University in Norfolk, Virginia. — Carolyn Rutledge, FNP-C, PhD, is a professor and associate chair of the graduate program in nursing as well as the director of the Doctor of Nursing Practice Program at Old Dominion University and maintains a clinical practice at Eastern Virginia Medical School in Norfolk. — Liana Orsolini, PhD, RN, ANEF, FAAN, is the care delivery and advanced practice system consultant for the Center of Clinical Excellence and Innovation for Bon Secours Health System, Inc in Marriottsville, Maryland. — Cynthia Marcum, DNP, FNP-BC, RNC, is an assistant professor at Jefferson College of Health Sciences in Roanoke, Virginia. — Debra Hain, PhD, APRN, ANP-BC, GNP-BC, FAANP, is an associate professor and Blake Distinguished Professor at Florida Atlantic University, Christine E. Lynn College of Nursing in Boca Raton, Florida and a nurse practitioner at the Louis and Anne Green Memory and Wellness Center and Cleveland Clinic Florida.

References 2. CDC focuses on need for older adults to receive clinical preventive services. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. http://www.cdc.gov/aging/pdf/cps-clinical-preventive-services.pdf. Accessed September 19, 2016. 3. More than 10 million people with Medicare have saved over $20 billion on prescription drugs since 2011. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Press-releases/2016-Press-releases-items/2016-02-08.html. Published February 8, 2016. Accessed September 19, 2016. 4. Wright LD, Zimbro K, Rutledge C, Marcum C. Relationship between health care practitioner characteristics and comfort level with the CMS Medicare annual wellness visit [unpublished manuscript, Doctor of Nursing Practice]. Norfolk, VA: Old Dominion University; 2015. 5. US Preventive Services Task Force. The Guide to Clinical Preventive Services: 2014. US Department of Health & Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality website. http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/clinicians-providers/guidelines-recommendations/guide/index.html. Published June 2014. Accessed September 19, 2016. 6. Advance care planning (ACP) as an optional element of an annual wellness visit (AWV). Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNMattersArticles/Downloads/MM9271.pdf. Published December 22, 2015. Accessed September 19, 2016. 7. CMS quality measure development plan: supporting the transition to the merit-based incentive payment system (MIPS) and alternative payment models (APMs). Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services website. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/MACRA-MIPS-and-APMs/Final-MDP.pdf. Published May 2, 2016. Accessed September 19, 2016. 8. Older adults. HealthyPeople.gov website. http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/older-adults. Accessed September 19, 2016. 9. Chung S, Lesser LI, Lauderdale DS, Johns NE, Palaniappan LP, Luft HS. Medicare annual preventive care visits: use increased among fee-for-service patients, but many do not participate. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(1):11-20. |