March/April 2021

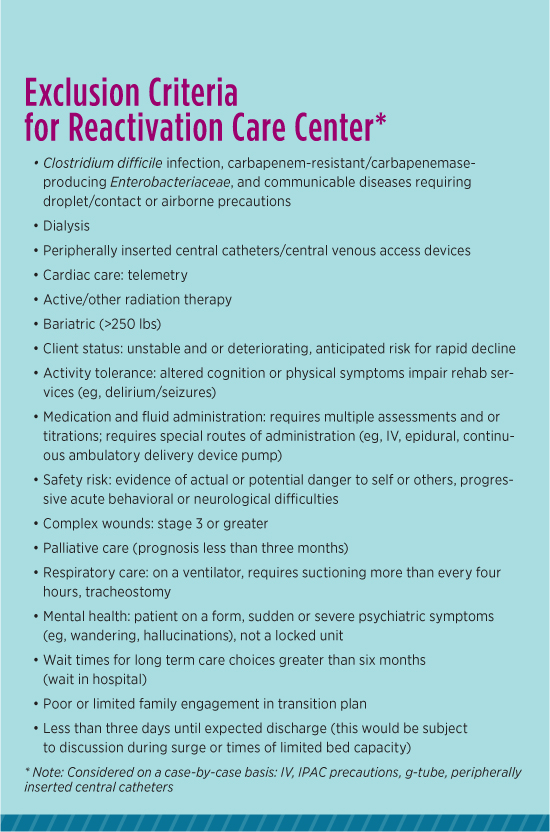

The Impact of COVID-19 in Long Term Care The COVID-19 pandemic continues to have detrimental effects around the world and in Canada. With millions of confirmed cases of COVID-19 worldwide and thousands in Canada, those most affected by the pandemic are older adults and the long term care (LTC) population.1,2 According to epidemiological data released in 2020 by the Government of Canada, the majority of COVID-19 cases are among individuals aged 60 and older, with a significant number of cases among LTC residents.3 Consequently, public health measures have been implemented across the spectrum of health care to protect the individuals most affected, support the health care system, and preserve essential resources. In preparation for a high volume of newly infected COVID-19 patients in Canadian hospitals, nonessential services and elective procedures were temporarily paused to increase acute care bed capacity, limit COVID-19 exposure, and prevent personal protective equipment shortages.4-6 Surgical activity was limited to “life or limb” procedures, with many cancer, cardiovascular, and other nononcological surgeries considered nonurgent.6 However, pressure to expedite discharge planning increased the likelihood of patients being discharged prematurely, with functional decline and reduced ability to perform self-care activities. Restrictions placed on community and home care rehabilitation services further contributed to reductions in physical function post discharge, placing patients at a 250% increased risk of hospital readmission or death.9 In addition to its impact on acute care, the COVID-19 pandemic has affected interprofessional inpatient rehabilitation facilities. Due to infection control guidelines, delivery of rehabilitation services in these facilities is complex. The American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation released a CAN (Conditions, Actions, Needs) report outlining guidelines for the delivery of care in inpatient rehabilitation facilities throughout the pandemic. The report advised pausing all group therapy classes and nonessential activities to ensure physical distancing, transitioning care from the gym to bedside when possible, adjusting the duration and frequency of therapy based on space and personal protective equipment constraints, and walking outdoors with higher-functioning patients to reduce the increased contact experienced when walking in hallways.10 It’s important to note that these recommendations listed above are derived from an American association and may not be relevant for rehabilitation facilities in Canada. To our knowledge, there’s no equivalent Canadian guideline. Moreover, transition from inpatient rehabilitation posed additional challenges as outbreaks of COVID-19 in LTC homes left patients and their families worried about increased risk of contracting the virus if transferred to these settings.8 This article explores the effects of the pandemic for older adults and the LTC population at the Reactivation Care Center (RCC), specifically the transition planning aspect of their care. Overview of the RCC Model • mobilization; The RCC provides care to patients who will benefit from enhanced services from an interprofessional team. The interprofessional team comprises a physician, nurse practitioner, nursing team lead, occupational therapist, physiotherapist, physiotherapy assistant, recreational therapist, speech and language pathologist, and registered dietitian. Many of their services are offered seven days per week to ensure that patients can focus on reactivating and meeting their mobility and functional goals. The interprofessional team provides patients with an environment that facilitates restoration of more normal routines through enhanced independence. Many of the patients are awaiting rehab or placement to LTC or retirement homes. The unit has a very strict inclusion and exclusion criteria, which are listed in the sidebar “Exclusion Criteria for Reactivation Care Center.”

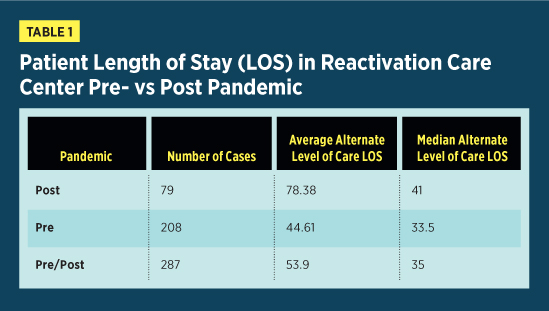

Demographics/Volumes of Unit Pre/Post COVID There are a number of observable changes in discharge destination and patient flow post pandemic. First, the average ALC length of stay increased from 44.61 days prepandemic to 78.38 days post pandemic, as seen in Table 1. Similarly, the number of ALC discharges decreased from 208 prepandemic to 79 post pandemic. These findings aren’t surprising, as COVID-19 outbreaks in many discharge destinations specific to the geriatric population necessitated enhanced infection control guidelines and strict policies regarding admission criteria. Consequently, as options for patient discharge decreased, length of stay increased.

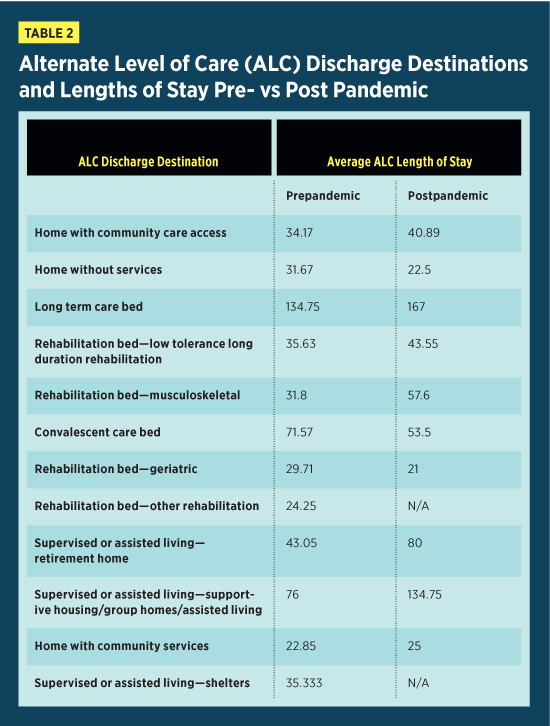

It’s useful to compare trends in ALC discharge destination prepandemic and post pandemic. Table 2 provides a summary of the discharge destinations and average ALC length of stay pre- and post pandemic. As expected, the total number of patients being discharged from ALC post pandemic decreased compared with prepandemic. Literature has shown that the growing number of COVID-19 cases in postacute care settings resulted in discharge to home being viewed as the best option.5 This is consistent with our data, as the most common discharge destination post pandemic was home with community care access services. Similarly, the length of stay of ALC patients being discharged home without services decreased from 31.67 days prepandemic to 22.5 days post pandemic. This reiterates that discharge home for ALC patients deemed functionally capable was expedited to increase bed capacity in these facilities. Additionally, the number of discharges to LTC increased from 16 prepandemic to 19 post pandemic. However, the ALC length of stay of patients awaiting LTC placement increased from 134.75 days prepandemic to 167 days post pandemic. This increase is expected, as rigorous policies regarding admission protocols and enhanced public health measures aimed at slowing the spread of the virus increased the complexity of the transition planning process. No patients were discharged to convalescent care post pandemic. This finding is expected, as many LTC homes stopped taking applications for convalescent care beds during the pandemic. Similarly, there were no report of patients discharged to supervised or assisted living, including retirement homes, supportive/group homes and shelters post pandemic. These findings are predictable, as ongoing COVID-19 outbreaks and the need to transform multipatient rooms into isolation rooms required many assisted living facilities to temporarily pause new admissions.

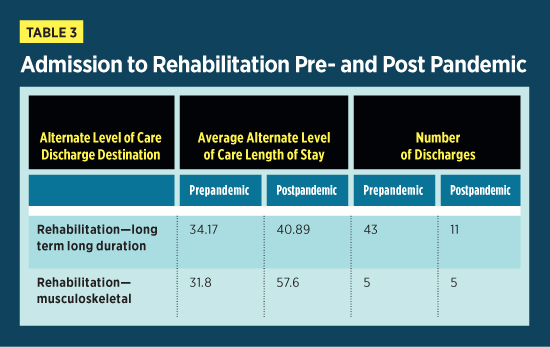

The number of patients discharged to inpatient rehabilitation facilities decreased significantly post pandemic as many inpatient rehabilitation facilities heightened patient screening protocols and reduced their bed capacity to enhance infection control. The number of ALC patients discharged to low tolerance long duration rehabilitation decreased from 43 prepandemic to 11 post pandemic. Correspondingly, patients were waiting longer for low tolerance long duration placement post pandemic compared with prepandemic. Likewise, the LOS of ALC patients awaiting placement to musculoskeletal rehabilitation increased from 31.8 days prepandemic to 57.6 days post pandemic.

Changes in Policies at RCC

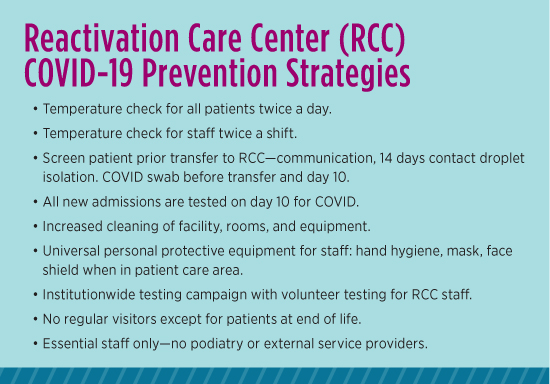

Fortunately, our unit didn’t have any positive cases, nor did we have any outbreaks confirmed. As part of our safety measures, the infection control team from the host hospital came to do a site visit. The main recommendation from this was for patients in the hallway to be masked. Level 1 masks were made available for patients who were sitting in the hallway as part of their socialization as well as their physical therapy. Another recommendation was for the staff to be voluntarily screened. An occupational health nurse came to offer this on site for convenience. There were also a number of opportunities to be mask fit tested for different models of N95 masks. In order to maintain regular communication, there were almost daily meetings of the host and partner hospital leadership teams. At the RCC, we had weekly meetings with our leadership team in conjunction with that of our base hospital. This allowed for regular, ongoing communication and updates about infection control strategies as well as review of any changes to the guidelines. This type of communication was particularly important, as a number of the partner hospitals did have confirmed outbreaks on their units. The host hospital ultimately decided to close all units to admissions until the outbreaks were clear. As a result, this affected our unit’s ability to accept new patients. Furthermore, new admissions required isolation for 14 days, and this functionally reduced our capacity by 30% to 40%. All of the rooms on the unit were designed to be semiprivate, but now many were then being used as private rooms for isolation purposes. Changes in Policies in Ontario LTC Facilities Active screening for COVID-19 symptoms and temperature checks were performed on all residents twice daily, in the morning and at night. For most of the pandemic up to this point, a negative COVID swab was required to be transferred to the home within 24 hours of obtaining the result for discharge to LTC and retirement home.12 New admissions to LTC or retirement living were permitted only if the facility wasn’t experiencing an outbreak, if the facility had adequate staffing and resources, if the home was able to provide appropriate accommodation for the patient to complete 14 days of self-isolation, and if the patient was able to be placed in a single- or double-occupancy room.12,13 Staff and resident cohorting policies were also implemented to prevent the spread of COVID-19. Resident cohorting was achieved by modifying accommodation to ensure physical distancing at all times, cohorting residents based on COVID-19 status, and converting rooms designated for other purposes to accommodation rooms. Cohorting of staff was achieved by designating specific patients or exclusive areas of the facility for staff to work in, as well as by limiting the number of work locations at which each staff member was employed.11 A community program called Home at Last that helps provide safe transport for patients back to their homes after an acute care state. Notably, this program required patients to have a negative COVID swab even though they were going back to their private homes. Lessons Learned on Transition Planning and Choices For those who were admitted and stabilized medically, transitional care became much more challenging. In some circumstances, LTC patients were sent to acute care to be stabilized because of limited staffing resources at the LTC facility. The focus of our population are those frail older adults for whom it’s unsafe to return home. Often, LTC would be a first choice; however, in the context of the pandemic, families attempted to find alternative solutions—increased private care in the home or placement in private retirement home facilities. Unfortunately, patients who were awaiting LTC placement prior to the COVID-19 pandemic ended up on our unit for a disproportionately long amount of time. One of the longest lengths of stay was more than six months due to logistical challenges. Even some of the hospital leadership staff members were redeployed to LTC to help reinforce infection control and other protocols for safety measures. Positively, this has warranted interest from our government, as well as from hospitals, to invest in the modernization of outdated LTC facilities, which is overall a positive outcome for our older patients. Once LTC facilities reopened, we were able to quickly transfer many of our patients to safe facilities that were COVID-free. However, as we face the second wave of this pandemic, time will tell if closures and outbreaks will happen again. — Pamela Liao, MD, CCFP (PC), is a hospitalist physician at the Reactivation Care Center. She is appointed in the division of geriatrics, department of internal medicine at St Joseph’s Health Sciences Centre and is an assistant professor in the department of family and community medicine at the University of Toronto. — Sarah Rydahl, BScH, BScPT, MSC, is a clinical coordinator at Unity Health Toronto. She has status only academic appointment to the department of physical therapy at the University of Toronto. — Izabela Dorocicz is a student at the University of Toronto physical therapy program.

References 2. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Government of Canada website. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/coronavirus-disease-covid-19.html. Updated January 18, 2021. 3. NIA Long-Term Care COVID-19 Tracker. https://ltc-covid19-tracker.ca/. Updated January 18, 2021. 4. Bettger JP, Thoumi A, Marquevich V, et al. COVID-19: maintaining essential rehabilitation services across the care continuum. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5(5):e002670. 5. Tahan HM. Essential case management practices amidst the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) crisis: part 2: end-of-life care, workers' compensation case management, legal and ethical obligations, remote practice, and resilience. Prof Case Manag. 2020;25(5):267-284. 6. Ontario Health. Recommendations for regional health care delivery during the COVID-19 pandemic: outpatient care, primary care, and home and community care. https://www.wrh.on.ca/uploads/ 7. Gitkind AI, Levin S, Dohle C, et al. Redefining pathways into acute rehabilitation during the COVID‐19 crisis. PM R. 2020;12(8):837-841. 8. Keeney T. Physical therapy in the COVID-19 pandemic: forging a paradigm shift for rehabilitation in acute care. Phys Ther. 2020;100(8):1265-1267. 9. Falvey JR, Krafft C, Kornetti D. The essential role of home- and community-based physical therapists during the COVID-19 pandemic. Phys Ther. 2020;100(7):1058-1061. 10. McNeary L, Maltser S, Verduzco‐Gutierrez M. Navigating coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid‐19) in physiatry: a CAN report for inpatient rehabilitation facilities. PM R. 2020;12(5):512-515. 11. Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Assess & restore guideline. http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/assessrestore/docs/ar_guideline.pdf. Published October 2014. 12. Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Directive #3 for long-term care homes under the Long-Term Care Homes Act, 2007. http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/publichealth/ 13. Ontario Health. Updated — a measured approach to planning for surgeries and procedures during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://www.ontariohealth.ca/sites/ontariohealth/files/2020-05/A%20 |