May/June 2017

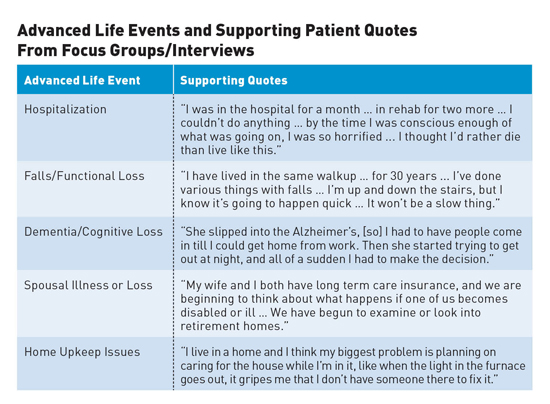

Lifespan Planning Promotes Successful Aging in Place It's important for providers to make patients aware of the necessity of planning for unforeseen events such as falls, hospitalizations, and caregiving needs, and sharing their wishes with their spouses and family members to ensure their fulfillment. Aging in place is a priority for many older adults.1-3 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines aging in place as the ability to live in one's own home and community safely, independently, and comfortably, regardless of age, income, or ability level.4 As a whole, older adults play a much needed role in their communities. Older adults retire later today than ever before, and approximately 45% of all adults over the age of 65 volunteer annually.5 Older adults who remain in their own homes have greater satisfaction, less depression, and maintain their physical function better than elders who reside in assisted living facilities or nursing homes.6-8 As the population matures, aging in place is no longer a simple outcome of being present in a home for elders. To successfully age in place, older adults must be safe, able to handle their needs, or harness technologies and find surrogates who can fulfill their needs.9-12 An individual living in his or her own single-family house is a common representation of aging in place.13,14 However, there are other permutations of aging in place, including what constitutes a home as well as a community. With choices such as independent living or assisted living, older adults are able to age in place in residential elder-dense communities.15-17 In addition, in order to successfully age in place, people depend on the success of their neighborhoods. As neighborhoods age, the nation is finding more naturally occurring retirement communities (NORCs). NORCs are communities in which 40% or more of the homeowners and renters are aged 65 and older.18,19 To enable aging in place among elder-dense communities, villages are popping up. Villages are grassroots, elder-driven organizations in which older adults assist other older adults to remain in their homes.20,21 Aging in place is not a one-size-fits-all concept; instead, it reflects the diversity of older adults. Preferences, needs, and access to services differ among older adults from varied rural or urban settings, income levels, sexual and gender identities (eg, lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender), and special circumstances (eg, adults who are caring for children with developmental disorders).22,23 With more options for elder living, aging in place can be as diverse as the individuals who comprise it. Impediments to Aging in Place The occurrence of advanced life events (ALEs) impedes the ability to age in place. A recent study identified elders' perceptions and planning toward ALEs that may impact their ability to remain in their own homes.26 Focus groups with 68 older adults (mean age 73.8 years), living in the community (rural, urban, and suburban), were conducted using open-ended questions about perceptions of future heath events, needs, and planning. Respondents identified five ALEs that impacted their ability to remain at home, including hospitalizations, falls, dementia, spousal loss, and home upkeep issues (see table).

Planning for Aging in Place Needs and Handling Emergencies Issues are multiplied when an aging primary caregiver, often a spouse, becomes ill or is hospitalized. Prior research has shown that older adults and their families commonly have no concrete back-up plan for a crisis or disaster situation involving the primary caregiver being unable to provide care.29 When an 80-year-old wife who cares for her 90-year-old spouse with Alzheimer's disease falls at home and is hospitalized, families must deal with both her hospitalization and the full-time supervision of her husband. As a result, when older adults become sick or experience an ALE, families must react to the emergency.26 While the older adult is incapacitated in a hospital bed, families select subacute rehabilitation facilities, consider placement in long term care institutions, or hire caregivers to assist after the older adult is discharged. Often families are making decisions without the knowledge of an older adult's preferences, as he or she has never had specific discussions about possible future needs. Subsequently, older adults may find themselves having little or no voice in their futures. Frequently, when ALEs occur, patients and their families look to their trusted health care providers for advice. As health care providers, we are repeatedly asked such questions as "Mom fell and is hospitalized now; do you know what we should do to help her get home? Do you know any good skilled nursing facilities? Does she need a caregiver, and how do I find one? How am I to pay for all of this?" After being a part of this conversation with each crisis, a health care provider may wonder: Why do we have to merely react to the aftermath of a crisis when we know that it might happen? Why do we fail to plan for these events? We know that older adults may be hospitalized at some point. There is a fair chance that they may fall. There is a significant possibility that their memories will worsen. Why can't older adults make decisions to age in place, just as we do for end-of-life planning? Facilitating Planning to Age in Place

It is a free, nationwide website tool. Through PYL, older adults and their loved ones learn about common ALEs that can impact their independence. Each section of PYL starts with a video, with subcategories providing information on what to expect and the types of resources available to support home needs. It can be highly personalized; users can log in and make specific choices for themselves. For example, by entering their residential zip code, users can identify the closest Area Agency on Aging, what services are provided there, what home caregiver agencies or services exist in the area, or what senior community groups are nearby. Some of the choices and information include the following: • What are the rehabilitation options following a hospitalization? • Am I prepared to return home after a hospitalization? • How can I connect with local services and resources such as in-home care, villages, and skilled nursing facilities? • What steps can be taken to help prevent falls? The website interface incorporates large font, high-contrast text and videos of older adults themselves discussing their personal experiences. After going through PYL, users can save their preferences for home services and revisit their choices at any time. As needs change, they may want to revisit certain home resource options or adjust their long-term plans. To support communication and involvement between older adults and their families, a summary of their long-term choices, with specifics on available home resources, can be printed or e-mailed to relevant parties. The communication component of PYL is crucial. Elders can make exceptional plans, but if they do not talk about their plans with others, their wishes may go unheard. For example, an older adult uses PYL and makes decisions about living with family in the future vs hiring caregivers. He or she can then e-mail these choices to his or her daughter, which can stimulate a conversation about future needs and expectations. Effectiveness of PlanYourLifespan.org Practical Means of Facilitating Lifespan Planning How can health professionals integrate PYL into their practices? Whenever the authors see an elder patient, they ask about all of the general end-of-life plans. Patients usually reply that they have it all figured out with a will, power of attorney, trust, etc. The authors then ask the following: • Have you thought about the 10 to 20 years before you die? • What plans, besides purchasing long term care insurance, have you made? • Will you live in your own home, or do you want to live somewhere else when you need help? Have you talked with your loved ones about your plans? • Here is a website [PYL] that will walk you through what you are going to need in the fourth quarter of life. In an ideal world every practice would have a social worker; however, this is not always the reality. Fortunately, several providers have commented that they think of PYL as a "virtual social worker" to connect people to resources. These resources can enable patients to continue living at home and provide other benefits. Dissemination of PYL Many health care providers talk about how they use PYL with their patients and their own parents—especially those whose parents live out of state. Some parents may not make this planning process easy on their children. They may say, "I'm healthy now; I'm never going to need any of that help,' or, 'I'm not going to get Alzheimer's, so why worry?' or, 'I plan to die in my sleep and before I ever need help.'" However, it is important to overcome these communication barriers and have a frank conversation about aging in place. Instead of postponing the conversation, we have something more concrete—a tool that will help facilitate the conversation about aging in place. PYL is currently being disseminated nationally and can be accessed freely. If you are interested in materials to distribute to your own group or organization, feel free to contact planyourlifespan@northwestern.edu. For all of us, here is to successfully aging in place now and in the future. — Andrea Cabello Cise, MD, is a graduating family practice resident at Presence St. Joseph Hospital in Chicago and will start her fellowship in geriatrics at UCLA in the fall. — Ziv Ofek is founder and CEO at the Center for Digital Innovation and the Healthy Aging Lab in Beer-Sheba, Israel. — Lee A. Lindquist, MD, MPH, MBA, is section chief of geriatrics at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago. References 2. Wagner L. Aging in place fuels growth in assisted living. Provider. 1995;21(10):54-55, 67-68. 3. Rosel N. Aging in place: knowing where you are. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 2003;57(1):77-90. 4. Healthy places terminology. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. http://www.cdc.gov/healthyplaces/terminology.htm. Updated August 14, 2013. Accessed March 2, 2017. 5. Ekerdt DJ. Frontiers of research on work and retirement. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2010;65B(1):69-80. 6. Sharifi F, Ghaderpanahi M, Fakhrzadeh H, et al. Older people's mortality index: development of a practical model for prediction of mortality in nursing homes (Kahrizak Elderly Study). Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2012;12(1):36-45. 7. Kang-Yi CD, Mandell DS, Mui AC, Castle NG. Interaction effect of Medicaid census and nursing home characteristics on quality of psychosocial care for residents. Health Care Manage Rev. 2011;36(1):47-57. 8. Zuidgeest M, Delnoij DM, Luijkx KG, de Boer D, Westert GP. Patients' experiences of the quality of long-term care among the elderly: comparing scores over time. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:26. 9. Gershon RR, Dailey M, Magda LA, Riley HE, Conolly J, Silver A. Safety in the home healthcare sector: development of a new household safety checklist. J Patient Saf. 2012;8(2):51-59. 10. Lindquist LA, Tam K, Friesema E, Martin GJ. Paid caregiver motivation, work conditions, and falls among seniors clients. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;55(2):442-445. 11. Lien LL, Steggell CD, Iwarsson S. Adaptive strategies and person-environment fit among functionally limited older adults aging in place: a mixed methods approach. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12(9):11954-11974. 12. Tomita N, Yoshimura K, Ikegami N. Impact of home and community-based services on hospitalisation and institutionalisation among individuals eligible for long-term care insurance in Japan. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:345. 13. Grimmer K, Kay D, Foot J, Pastakia K. Consumer views about aging-in-place. Clin Interv Aging. 2015;10:1803-1811. 14. Taira ED, Carlson JL. Aging in Place: Designing, Adapting, and Enhancing the Home Environment. New York, NY: Routledge; 2000. 15. Henwood BF, Katz ML, Gilmer TP. Aging in place within permanent supportive housing. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;30(1):80-87. 16. Zimmerman S, Sloane PD, Eckert JK. Assisted Living: Needs, Practices, and Policies in Residential Care for the Elderly. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2001. 17. Vasara P. Not ageing in place: negotiating meanings of residency in age-related housing. J Aging Stud. 2015;35:55-64. 18. Rivera-Hernandez M, Yamashita T, Kinney JM. Identifying naturally occurring retirement communities: a spatial analysis. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2015;70(4):619-627. 19. Greenfield EA. Community aging initiatives and social capital: developing theories of change in the context of NORC Supportive Service Programs. J Appl Gerontol. 2014;33(2):227-250. 20. Greenfield EA, Scharlach AE, Lehning AJ, Davitt JK, Graham CL. A tale of two community initiatives for promoting aging in place: similarities and differences in the national implementation of NORC programs and villages. Gerontologist. 2013;53(6):928-938. 21. Scharlach A, Graham C, Lehning A. The "Village" model: a consumer-driven approach for aging in place. Gerontologist. 2012;52(3):418-427. 22. Sullivan KM. Acceptance in the domestic environment: the experience of senior housing for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender seniors. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2014;57(2-4):235-250. 23. Crist JD, Speaks P. Keeping it in the family: when Mexican American older adults choose not to use home healthcare services. Home Healthcare Nurse. 2011;29(5):282-290. 24. Gillsjö C, Schwartz-Barcott D, von Post I. Home: the place the older adult cannot imagine living without. BMC Geriatr. 2011;11:10. 25. Yondorf B, National Conference of State Legislatures. Aging in Place: State Policy Trends and Options. Denver, CO: National Conference of State Legislatures; 2005. 26. Lindquist LA, Ramirez-Zohfeld V, Sunkara P, et al. Advanced life events (ALEs) that impede aging-in-place among seniors. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2016;64:90-95. 27. Keenan TA. Home and community preferences of the 45+ population. AARP website. http://www.aarp.org/research/topics/community/info-2014/home-community-services-10.html. Published November 2010. 28. Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics. Older Americans 2012: key indicators of well-being. https://agingstats.gov/docs/PastReports/2012/OA2012.pdf. Published June 2012. 29. O'Sullivan T, Ghazzawi A, Stanek A, Lemyre L. "We don't have a back-up plan": an exploration of family contingency planning for emergencies following stroke. Soc Work Health Care. 2012;51(6):531-551. 30. Lindquist LA, Ramirez-Zohfeld V, Sunkara P, Forcucci C, Cameron KA. PlanYourLifespan.org — an intervention to help seniors make choices for their 70's, 80's, 90's: results from a PCORI funded randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;29(S1):S97-S98. |