Summer 2025

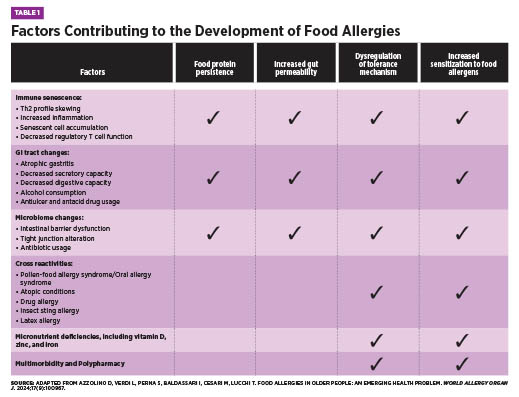

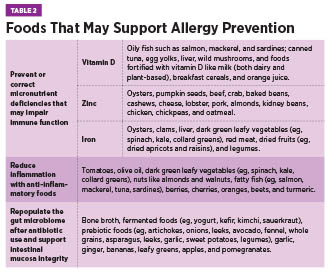

Summer 2025 Issue The Late-Onset Allergy Puzzle Understanding Food Allergies in the Elderly Although food allergies are often considered a childhood concern—frequently believed to resolve with age—recent evidence reveals that food allergies can develop at any point in life and may persist indefinitely. In fact, emerging data suggests that a cow’s milk allergy is as common in older adults as it is in children.1 Diagnosis in older adults can be especially challenging due to age-related changes that alter symptom presentation and/or food allergy development. These changes include immunosenescence, chronic low-grade inflammation, reduced gastrointestinal (GI) function, micronutrient deficiencies, and use of multiple medications.1 In addition, other conditions common amongst elderly individuals have similar symptoms to food allergies, sometimes leading to misdiagnosis.2 As allergies have continued to rise globally, the World Health Organization now classifies them among the top four chronic diseases. Combined with an ageing population, allergic disorders will become increasingly frequent amongst older adults.1,3 This article will explore why geriatric health care practitioners must be equipped to recognize the unique factors that contribute to food allergy development in older adults, understand their clinical presentation and diagnostic challenges, and know how best to implement effective management strategies within the care team to support patient health and quality of life. Epidemiology and Prevalence The discrepancy between diagnosed and self-reported food allergies may result from underreporting or symptom misattribution. In older adults, food allergy symptoms—such as GI distress, abdominal pain, malabsorption, and skin disturbances—often overlap with more common conditions like irritable bowel syndrome, gastroesophageal reflux disease, or idiopathic urticaria. For example, eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE), a food allergy-related condition marked by dysphagia, is especially relevant in older adults, who often have swallowing difficulties for other reasons.1 Similarly, aging skin, prone to dryness and itching, may mask or mimic allergic skin reactions.2 Some adults may have long-standing allergies that worsen over time, while others develop allergies later in life. Emerging food allergy conditions in adults include EoE, food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome, and alpha-gal syndrome—a red meat allergy linked to IgE antibodies against the alpha-gal sugar.1 Pollen-food allergy syndrome, formerly oral allergy syndrome, occurs more often in adults than children due to respiratory allergen sensitization and affects 13% to 58% of adults, depending on location.5,6 Epidemiologic data reveals key trends. Women are nearly three times more likely than men to develop food allergies, and prevalence is higher in adults over age 60 and those identifying as nonwhite or Hispanic, even after controlling for socioeconomic status. Additional adult-onset risk factors include environmental, medication, insect, or latex allergies; chronic urticaria; and other chronic conditions.4 In order of frequency, the most common adult-onset allergens are shellfish, milk, peanuts, tree nuts, fin fish, egg, wheat, soy, and sesame, whereas childhood-onset allergies more often involve eggs, peanuts, and milk.1 Unlike children, adults are less likely to outgrow their allergies, which tend to persist.1,4 Because symptoms overlap with other conditions and food allergies are often viewed as a childhood condition, clinicians may overlook them in older adults. Immunosenescence and the Aging Immune System Both the innate and adaptive arms of the immune system, as well as their interaction with each other, undergo substantial alterations as people age.3 Hallmarks of immunosenescence include an increased number of memory and senescent lymphocytes, a reduction in naïve lymphocytes, hematopoietic stem cell dysfunction, progressively lower serum levels of total IgE due to reduced output of thymic T-cells, and impaired function of immune regulatory cells.1,3 The balance between T-helper cell subtypes also shifts. With aging, there is a decline in overall T-cell production and a skewing of the T-helper response toward Th2 dominance.2 While Th2 cells are considered anti-inflammatory in some contexts due to their production of cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-10, this type of T-helper cell is also central to allergic responses by recruiting and activating mast cells, eosinophils, and IgE-producing B cells.2,8 As well, peripheral T cells in older adults tend to produce more inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-17, which may further promote allergic sensitization and increase the likelihood of developing food allergies.2 Decreased mitochondrial function and ability to respond to stress also contribute to lowered immune system function.3 Additionally, micronutrients which are essential for proper immune function, including iron, zinc, and vitamin D, are often deficient in older adults, which can impair immune regulation and exacerbate allergic responses.3 These immune changes, whether caused by immunosenescence, micronutrient deficiencies, or impaired mitochondrial function, increase susceptibility not only to infections and autoimmune disease but also to chronic inflammation and allergic reactions in older adults.3 Pathophysiology of Late-Onset Food Allergies Nonimmune-mediated reactions include enzyme deficiencies (eg, lactose intolerance), pharmacologic effects (eg, caffeine sensitivity), toxin exposures (eg, scombroid poisoning), and sensitivities to chemical additives like sulfites.1,5 Though these differ from allergies in mechanism, symptom overlap can occur, and both often improve by avoiding triggering foods.5 The aforementioned age-related changes to the immune system are an important part of the pathophysiology of food allergy development in older adults. Chronic inflammation and age drive changes in the GI tract as well. The higher levels of Th2 cytokines negatively affect the tight junctions of the intestinal wall, leading to impaired intestinal barrier function.1,3 Mucosal aging compromises the ability of epithelial tight junctions and gut-associated lymphoid tissue to prevent allergic sensitization. Levels of secretory IgA, hyaluronic acid, and mucus also decline, weakening the defensiveness of the gut barrier against potential antigens.2 Because food allergies are triggered by a weakened gut barrier and an abnormal immune response, older adults are at increased risk for their development. In addition, frequent use of antiulcer drugs or antacids and decreased stomach acid from atrophic gastritis may lead to incomplete protein digestion, allowing intact proteins to reach the intestinal wall.3 Ongoing exposure to these antigens can trigger the development of IgE antibodies and increase reactivity to food allergens.2,3 Environmental factors, food quality, and microbiome alterations may further sustain low-grade inflammation and allergic responses.3 With the age-related changes to the GI and immune systems, microbiome, allergic reaction severity, micronutrient deficiencies, comorbidities, and use of multiple medications, older adults may struggle to maintain oral tolerance to harmless substances such as food proteins. At the same time, the immune system may still mount strong allergic responses to perceived threats.2 This creates a vicious cycle in which internal chronic inflammation compromises the epithelial barrier, allowing allergens to enter the GI wall, further fueling inflammation and immune activation in a self-perpetuating and ever-worsening cycle. Clinical Presentation in Older Adults Though anaphylaxis is less common in this population, it carries a higher risk of poor outcomes due to age-related vulnerabilities—particularly among those with cardiovascular disease. The release of anaphylaxis mediators from mast cells can significantly impact cardiac function, worsening the prognosis.2 In older adults, symptoms associated with a food allergy can be caused by other conditions. For example, urticaria can also stem from nonallergic causes such as hematologic or autoimmune conditions, highlighting the importance of determining the underlying etiology for proper treatment.2 Diagnosis and Evaluation Skin prick testing remains a first-line diagnostic tool for food allergies; however, age-related changes such as skin atrophy, photoaging, and reduced mast cell numbers can reduce skin reactivity and impair test interpretation. Additionally, medications frequently used in this population, such as antihistamines, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and tricyclic antidepressants, may blunt skin responses, further complicating diagnosis.1 In such cases, serum-specific IgE testing is often used as a second-line diagnostic method. Yet, total IgE levels tend to decline after age 50, and some researchers caution against applying standard diagnostic cut-offs in the older population without adjustment for age-related changes.1 If initial tests suggest an allergy, an oral food challenge or elimination diet—conducted under clinical supervision—may help confirm the diagnosis. These methods provide valuable information when correlated with medical history and lab results.1 Clinicians must also recognize that certain medications may mask symptoms of food allergy, delaying or obscuring diagnosis.2 Furthermore, distinguishing between food allergy, intolerance, and sensitivity is often difficult. Older adults may misattribute symptoms to an allergy when they stem from nonimmune causes. For example, GI discomfort after consuming cow’s milk may be due to lactose intolerance rather than an IgE-mediated allergy.1 In one study of adults aged 65 and older with atopic dermatitis, 25% had positive food skin prick tests and frequently reported coexisting IgE-mediated conditions such as rhino-conjunctivitis, asthma, and COPD. Notably, 35% of these individuals also experienced GI symptoms like dyspepsia, abdominal pain, diarrhea, or constipation—symptoms that may be associated with undiagnosed food allergies.7 A nuanced, individualized approach is essential to accurately identify food-related reactions in this age group. Management and Interventions Once allergens are identified, nutrition counseling becomes essential. A registered dietitian nutritionist (RDN) can provide practical guidance on how to avoid allergens, interpret food labels, and select satisfying alternatives to prevent nutritional deficiencies or unnecessary food restrictions. This is particularly important, as elimination diets without professional oversight may lead to undernutrition, sarcopenia, and frailty in older adults.1 Monitoring by the health care team is crucial during dietary transitions. Worsening changes in weight, skin reactions, GI symptoms, and micronutrient status may indicate accidental exposure or a poorly balanced diet.1 Adequate intake of nutrients such as vitamin D, zinc, and iron is especially important, as deficiencies in these nutrients may play a role in allergy development or symptom exacerbation. Reducing alcohol intake while increasing foods that support intestinal health may also improve GI integrity and reduce sensitization risk.1,3 All older adults diagnosed with food allergies should be prescribed epinephrine due to the potential for more severe reactions over time. However, factors such as cognitive decline, impaired motor function, or living alone may limit a person’s ability to self-administer this medication.3,4 Health care providers should assess these limitations and consider medication interactions—especially with beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, and neuroleptics—that may complicate epinephrine use.2,3 Finally, clinicians should evaluate how medications such as antacids, glucocorticoids, antibiotics, and antiulcer drugs may compromise GI function and contribute to sensitization, considering alternatives where feasible.2 Appropriate management of food allergies enhances quality of life and reduces the risk of malnutrition and adverse outcomes. Final Thoughts — Stephanie Dunne, MS, RDN, IFNCP, is an integrative registered dietitian, freelance writer, and owner of Feed Your Intention in St Petersburg, Florida.

References 2. De Martinis M, Sirufo MM, Viscido A, Ginaldi L. Food allergies and ageing. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(22):5580. 3. De Martinis M, Sirufo MM, Ginaldi L. Allergy and aging: an old/new emerging health issue. Aging Dis. 2017;8(2):162-175. 4. Gupta RS, Warren CM, Smith BM, et al. Prevalence and severity of food allergies among US adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(1):e185630. 5. Solymosi D, Sárdy M, Pónyai G. Interdisciplinary significance of food-related adverse reactions in adulthood. Nutrients. 2020;12(12):3725. 6. Carlson G, Coop C. Pollen food allergy syndrome (PFAS): a review of current available literature. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019;123(4):359-365. 7. Chello C, Carnicelli G, Sernicola A, et al. Atopic dermatitis in the elderly Caucasian population: diagnostic clinical criteria and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59(6):716-721. 8. Romagnani S. Regulation of the development of type 2 T-helper cells in allergy. Curr Opin Immunol. 1994;6(6):838-846. |