Summer 2025

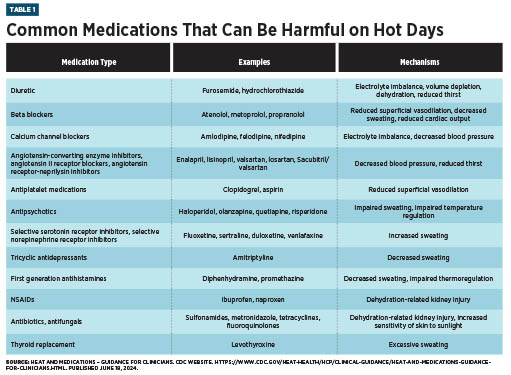

Summer 2025 Issue The Last Word: Aging and Heat Are a Dangerous Combination Extreme summer heat is a growing problem across the United States, limiting outdoor activities and contributing to health risks for vulnerable populations. Older Americans are especially affected by hot weather: According to a 2023 analysis of Medicare beneficiaries, higher peak daytime temperatures and reduced overnight cooling in urban areas can lead to an elevenfold increase in heat-related hospitalizations.1 Health care providers have an important role to play in reducing the incidence of heat-related complications among older patients, even in climates where the temperatures are less extreme. When assessing a patient’s risk for heat-related health concerns, it helps to focus on the three Ps: physiology, psychology, and pharmacology. Understanding these factors and how they intertwine can help providers formulate more effective interventions. Physiological changes associated with aging include decreased renal function, lower total body weight, lower plasma volume, decreased cardiac output, and reduced thirst. These can affect sodium/water balance and the body’s ability to maintain homeostasis and thermoregulation. Older patients have a decreased ability to sweat, as well as decreased blood flow to the skin and extremities. Elevated glucose levels in some patients can increase urine output and further predispose them to dehydration. It is important to educate patients about how their susceptibility to heat changes with age, as longstanding habits and behaviors can become more dangerous from one summer to the next. As anyone of a certain age can attest, there tends to be a disconnect between how old we feel and how old we actually are. There is even a term for it: subjective age bias. This can lead to a certain degree of denial regarding the risk of extreme heat. Anxiety can also play a role. For example, some individuals may be wary of staying hydrated due to concerns about bladder control or worry about the cost of using air conditioning. In addition, it’s important to remember the patient’s psychology, as dementia or other mental health concerns can reduce patients’ ability to perform self-protective behaviors when the mercury rises. Finally, older patients’ medications may put them at risk for heat-related morbidity. A 2020 study found that heat waves were associated with a 21% to 33% increased risk of heat-related hospitalizations over a five-year period.2 Many common medications increase the body’s sensitivity to heat and contribute to heat-related hospitalizations.2 The risk increases with the number of medications prescribed, as there are numerous mechanisms by which medications increase the risk of heat-related events. These mechanisms include the following: • dehydration from increased diuresis and impaired thirst; Even seniors who stay cool are vulnerable to adverse events if their medications become exposed to extreme heat. In general, unless specifically labeled to be refrigerated, medications should be stored at a controlled room temperature, typically between 68°F and 77°F (20°C to 25°C).3 Extreme heat, especially when medications are left in vehicles, can reduce the effectiveness of some medications or delivery devices. Capsules may melt, and liquids may evaporate. Medication stored in injectable “pens” (such as insulin or epinephrine) can degrade quickly, while delivery devices like inhalers can burst when exposed to high temperatures. Preventing Hot Weather Problems

Most older patients should be encouraged to drink water even when they are not thirsty. They should also be counseled on minimizing alcohol use, since alcohol has diuretic effects and can impair the perception of heat and thirst. All patients should be reminded of the proper ways to store their medications and advised to talk with a pharmacist if they have concerns about their medications being exposed to heat. These strategies can help — Caren Martin, PharmD, BCGP, is a board-certified geriatric pharmacist and senior clinical manager at Enclara Pharmacia, where she helps hospice teams monitor pharmacy utilization and develop initiatives to improve quality and manage costs.

References 2. Layton JB, Li W, Yuan J, Gilman JP, Horton DB, Setoguchi S. Heatwaves, medications, and heat-related hospitalization in older Medicare beneficiaries with chronic conditions. PLoS One. 2020;15(12):e0243665. 3. United States Pharmacopeial Convention (USP). General chapter <659>: packaging and storage requirements. Rockville, MD: USP; [2017]. 4. Westaway K, Frank O, Husband A, et al. Medicines can affect thermoregulation and accentuate the risk of dehydration and heat-related illness during hot weather. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2015;40(4):363-367. |